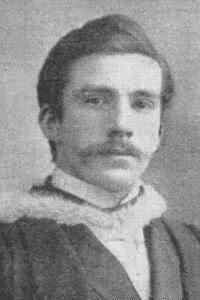

Malcolm Sterling Mackinlay and Vowels

If you've rummaged around this blog, you may have noticed a book in the Library section titled The Singing Voice and Its Training.

Written by Malcolm Sterling Mackinlay (1876 - 1952), the son of Antoinette Sterling (see previous post), The Singing Voice and Its Training was the first book to appear after the death of Manuel Garcia in England which detailed the latter's method from a technical standpoint.

A concert artist who embarked on a career as voice teacher, Mackinlay published his 189 page book on singing in 1910 at the age of 34. (Curiously, 1910 was also the same year that Manuel's sister Pauline Viardot-Garcia died.) While quoting liberally from Garcia's writings, Mackinlay also clarifies certain matters. One is "rounding," that is, the use of the soft palate in singing.

The Placing of the Voice

If the hints be followed and the faults avoided which have been given on the preceding pages, the pure emission of the tone which will result should in itself bring a correct "placing" of the voice. All that remains is to follow the old Italian advice, "Bisogna cantare sul fior delle labra:" form the tone, as it were, on the very edge of the lips. By this it is meant that, when the voice is properly placed, there will be a sensation of the tone vibrating in the front of the mouth above the middle teeth.

It will be found that by the air striking the hard palate above the front teeth, with the tongue lying motionless, a very rich volume of tone will result, and the cavity of the mouth, acting as a sounding-board, will enlarge with the wave of sound. In order, therefore, to have the voice properly placed, we must try mentally to get a sensation of directing the tone to the front of the mouth and of singing on breath. An aid to this may found in humming sustained notes, by which means the vibrations in the front of the mouth will make themselves very noticeable. After doing this, open the mouth and repeat the same so as to obtain similar sensations. It should not be long before this results in the proper placing of the voice, after which it will be well to abandon all further humming, as this practice is not considered a good one for singers.

As already explained, the various vowels are formed by the tongue taking certain positions in the mouth. In speaking of the rounding of notes, we will for the moment confine ourselves to the "first" primary vowel, A, which is formed by the tongue being kept flat and limp. Now it will be found that the A is capable of certain varying shades of quality or timbre, which principally depend of the height of the soft palate. When the palate is lowered, the vowel attains a clear, open quality, and when it is raised, as in yawning, the vowel takes on a dark, closed timbre, resembling aw. It is possible as an exercise to start a not on a very open quality of A, and then gradually to raise the palate till it reaches its top limit. During the process, the vowel will gradually take on a darker, more closed quality, till finally it reaches aw or o.

The process of raising the soft palate we term "rounding" the vowel, and that of lowering the palate we term "opening" it.

If we take the other vowels, we shall find that they are capable of similar changes. Thus, if we take E with a clear timbre and then gradually raise the palate, the vowel will be rounded more and more till it approximates to the French eu (as in "her"); I, similarly treated, approximates to the French ü (German = ü); while O approximates to oo, as in "who."

The darker, closed timbres of vowels display much richer quality of tone, and for this reason there are singers (usually with low-pitched voices) who adopt it entirely, singing invariably in "closed" timbre. Others, again (usually with high voices), sometimes pin their faith entirely to "open" timbre, and never sing except with "clear" notes. I have indeed heard two singers, champions of such opposite methods, discuss the matter thus—

"What style of singing do you go in for?"

"I always sing with closed production."

"Oh, do you? You ought to go in for the pure Italian method of singing with open production."

Of course nothing could be more ridiculous than such remarks, which merely display the speaker's ignorance on the subject of "open" and "closed" timbres. As singers we do not adopt very "open," or very "closed," or a middle course of fairly rounded tones, but we make use of all the possible shades of quality lying between the two extremes, according to the expression of the various phrases.

The reason for this is, that every feeling which we experience has for its expression a certain definite quality of voice, and this quality, if we analyse it, consists of a certain definite degree of "open" or "closed" quality, combined with a certain definite degree of "ringing" or of "veiled" quality. The former effect, as we have seen, is brought about by the degree of raising of the soft palate, the latter by the action of the vocal cords, and the degree of their perfect or imperfect closing between the vibrations. Hence, in one phrase the singer may be using an "open ringing quality." and in the next a "closed veiled quality." It all depends on the feeling to which we wish to give expression.

Let it not be thought that these various qualities are entirely confined to the singing voice. On the contrary, they are equally a part of the speaking voice. If we are happy, our speaking voice involuntarily takes on an "open" ringing quality; when we are miserable, it takes on a very "closed" veiled quality. We do not think of the mechanism by which we transmit the feeling into the voice, but we do it naturally. So equally all the other feelings have a definite quality of voice by which they are expressed: love, anger, fear, hope, etc.

For the ordinary practice of exercises in technique (scales, etc) the student will choose a middle quality of vowel, inclining to the "open," rather than to the "closed," but he will find it advisable occasionally to practice with other degrees of open and closed qualities, and to use the already suggested exercise of passing from one extreme of a vowel to the other on the same note, A to o, E to ue, etc; only by this can proper preparation be made for the expressive rendering of songs which is the final aim of the singer.

—From The Singing Voice and Its Training by Malcolm Sterling Mackinlay, p. 123-127

If you are like me, you are probably going to try this exercise out, which is very revealing. As a prerequisite, it might be good to keep in mind Mackinlay's instructions on how each vowel is made.

For A, let the tongue be flat and limp, the vocal arch expanded.

For the open E, expand the vocal arch and raise the tongue slightly in the middle.

For the closed E, the tongue should be still further raised, and it's edges should touch the upper teeth at the sides.

For I, (ee), the distance between the tongue and the palate should be still further reduced, while its edges are pressed between the upper and lower teeth at either side.

For the open O, the vocal arch is expanded and the tongue hollowed at the back.

For the closed O, there is a very slight rounding of the mouth, and considerable expansion of the vocal arch.

For U (oo), the mouth is slightly rounded as in O, and the vocal arch is still further expanded, the soft palate being rather more raised.

It will be observed that in the proper formation of these vowels, the tongue does all that is required, excepting in the case of A, O, and U, where it receives assistance from the expanding of the vocal arch. It will be found a good plan to learn to think the vowels without moving the parts of the mouth which produce them, since this mental preparation helps us when we come to the actual singing of them.

—From The Singing Voice and Its Training by Malcolm Sterling Mackinlay, p. 103-104

The careful reader will notice that Mackinlay makes the assertion that raising of the soft palate effects the ringing quality of the voice, while the action of the vocal folds (they were called cords or chords before scientists starting referring to their appearance when fully open) is responsible for its veiling. It's now known that the formation of the vocal tract and the action of the vocal folds are interdependent. Specifically, it is the narrowing of the glottis in relation to the size of the pharynx (1 to 6) that enables ring, also called the Singer's Formant. Of course, Mackinlay is correct: it is possible to raise the soft palate and at the same not bring the vocal folds closely together, thus bringing about a veiled, even breathy, quality (yes- in case you are wondering the larynx does descend a bit for the singer to pull this off). What is this called?

Crooning!

Crooning is a wonderfully warm & engaging sound, which singers like Bing Crosby and Max Raabe have excelled. Amplification makes this style possible. But it's not Bel Canto where great amplitude with ease is sought at every dynamic level.

If you can find Mackinlay's book at your nearest library it is well worth the time and effort.