The Garcia School: Clifton Cooke & Practical Singing

February 10, 2010

A very curious old book arrived in my mailbox from England this past summer. Its author—Mr. Clifton Cooke (1867-1938) taught voice in London and was a student of Manuel Garcia and Charles Santley, the latter a highly esteemed Victorian baritone.

I use the word curious because Clifton Cooke's book Practical Singing (1913) contains a pictorial representation of an old-school teaching that I have never seen anywhere else.

Light and shade in singing do not consist of singing passages loud and soft alternately; they consist in using various colours of the voice to suit the sentiment of the words.

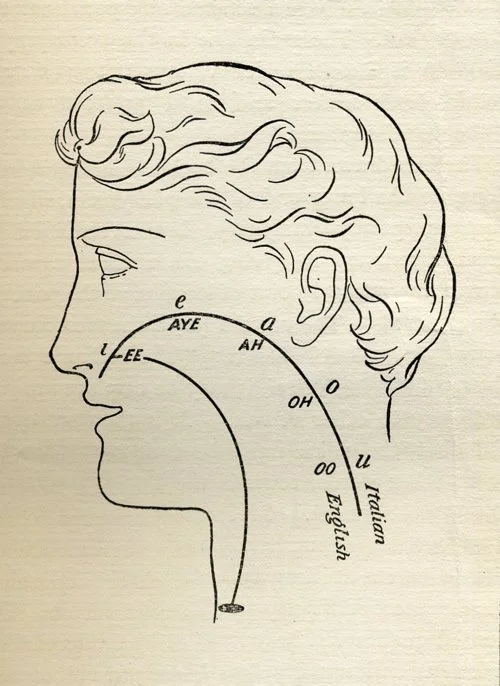

With this statement to guide us, a clear conception of the technique involved is the acquirement of command of tone-colour is of the utmost importance. The Italian School of Singing has handed down a vowel scheme of especial value in this respect. The main line in the accompanying diagram is known under various titles; the arco vocale, ponte contore, and as I prefer to call it, "the vowel segement."

The line drawn from the back of the upper teeth down to the lower end of the pharynx is, like the equator, purely imaginary, but nevertheless of great assistance in giving the student a visible idea of the natural point of location of the principal vowel sounds. The vowel I (ee) is the most forward vowel, or as Garcia has it: "The Italian I (ee) being the most ringing vowel, it may be employed to give brilliancy to other vowels." It is therefore essential that the voice must be trained "forward," or in other words, towards the I (ee) position on the vowel-segment. Of course the vowel I (ee) is susceptible of many timbres, and the brightest timbre must at first be cultivated. p. 42

A little later on in the text, Cooke emphasizes that training the vowels "forward" is the first work of the student, which leads—in due course—to the acquisition of the frontale voice.

The frontale voice has always been regarded by the Italian School as the foundation of the vocal structure, and many months may be profitably devoted to its development. p. 53

When the solid foundation of the voice has been laid with the frontale tone, the cultivation of the centrale, head voice, or mezza voce, as it is variously called, may be entered upon. It can be safely said that the centrale voice will be present as soon as the foundation has been truly laid. p. 54

According to Cooke, it might take months before the frontale and centrale voices can be emitted with ease in all the range of the voice. He tells the reader that it is only when this technical ability has been accomplished that single tone exercises for the messa di voce are to be given—the acid test for the mezza voce being the student's ability to swell the tone without slipping into the frontale voice. (A previous post on the Garcia School teacher Emi de Biloli, who utilized the phrase con la fronte, contains further information on singing "forward.")

Interestingly, the messa di voce was the first exercise that Cooke's teacher, Manuel Garcia, gave the student in A treatise on the art of singing (1847). With the aforementioned technical requirements by Cooke in mind, it is safe to assume that Manuel Garcia's inclusion of the exercise at the beginning of his own book is no indication of its simplicity.

Cooke gives the reader the distinct impression that learning to sing beautifully is a lot of work. Margaret Harshaw used to say: we work hard to make things simple.

Enjoy the drawing. It gives one a lot to think about. My take? It's all about listening.

Addendum: Sept 28th, 2024

Since the post above was written in February 2010, I have found myself pulling Cooke’s book from the shelf and showing singers his “vowel segment” graphic, which gives one a clear picture of what must be done.

I never say, “Put the vowels forward,” “You must sing forward,” or any such nonsense since there is no putting or pushing the voice anywhere.

“Putting” is not “listening.” And active listening to vowel quality is a requirement. A singer who wants a ringing voice must learn to breathe, form a tone, and create “pure vowels.”

This is the language of the old school. It requires listening for feeling and a feeling for listening.

But back to Mr. Cooke.

I found the following letter written to The Musical Times in 1936, two years before Cooke left this earthly plane at 71. In the end, he was a defender of the principles of the old Italian school and a promoter of his work, which you can find on the Download page.

The Science of Voice Production

Sir, — The report of the lecture entitled ‘The Science of Voice Production’ by Dr Richardson of Armstrong College, Newcastle-on-Tyne-, is yet another contribution to this everlasting subject. Curiously enough, Dr. Richardson can shed no light upon the matter. He admits that he does not profess to be a trained singer. As a trained singer myself, I take the liberty of laughing at his extraordinary lucubration. The learned Doctor simply ‘out-Herods Herod’ in the matter of fresh phraseology. Take, for instance, ‘we must first enumerate the constituent parts of the Voice-Producing System,’ &c., ‘These vibrations may be seen with a combination of a laryngoscope and the stroboscope,’ &c. As a result of prolonged training with such masters as Manuel Garcia, Charles Santley, De Pina, Palmiere, Landi, &c, I have evolved and taught a method which is fully described in my book ‘Practical Singing.’ Many years ago I challenged a scientific teacher of voice production (the author of a book entitled ‘Science and Singing’) to make a dead cock crow without the aid of his vocal cords. The gentlemen in question did not accept my challenge, although my friend, the late distinguished surgeon Forbes Ross, was present at the lecture to attend to the surgical side of the experiment.

It is strange that all the best singers in the world have been trained by teachers who in their day were good singers themselves. Even Melba owed her training to Signor Cecchi, although she very ungratefully tried to vamose from Melbourne without paying the old Italian singer his fees. (‘Melba.’ A Biography by Agnes G. Murphy. p 19.)

— Clifton Cooke, “The Science of Voice Production,” The Musical Times, August 1936, p. 740.