Herman Klein on Edouard de Reszke

THE MUSICAL TIMES- July 1, 1917

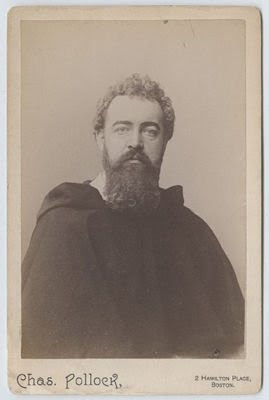

EDOUARD DE RESZKE: THE CAREER OF A FAMOUS BASSO, 1855*-1917, by Herman Klein.

In the days when the De Reszkes came upon the scene there were giants of the operatic stage- giants beside whom it took time for new-comers, however gifted to grow level in stature. To strive to compete with the great singers until after long years of hard work and experience in the theatre was hopeless and out of the question. Thus Jean de Reszke, who still lives and teaches in Paris (he is nearly six years older than was Edouard), was singing in London as a baritone in 1974, achieving brilliant failures because he was out of his element, a full decade before he made his first big success as a tenor in Paris, and thirteen years prior to the memorable Harris season at Drury Lane, when he and his brother at last really came into their own, and laid the foundation of their universal fame.

For Edouard de Reszke had also been here before. With a four years' stage career behind him he had made his début at Covent Garden in 1880 as Indra in Massenet's 'Roi de Lahore', a novelty of the previous season, with Gayarre, Lassalle, and Albani in the principle parts. But the Polish basso cantante did not set the Thames on fire. He was recognized as an artist belonging to the genius 'useful.' Above all, his rich, full voice had a haunting quality, a penetrating beauty of timbre, which it owed quite as much to nature as to art. During the last five seasons of the Gye régime he appeared in an extensive round of characters, proving always competent, always acceptable, always hardworking and sincere. Surviving habitués of that period- among them the present writer- easily recollect the delightful Italian purity of his legato, the charm of his phrasing, the ease, distinction, and authority of his style. In parts like St. Bris ('Les Hugeunots'), the Count Almaviva ('Figaro'), Walther ('Guilaume Tell'), Basilio ('Il Barbiere'), and Alvise ('La Gioconda'), he was quite unsurpassable. But his Mephistopheles had yet to mature; there the memory of the 'giants' was still vivid and hard to efface.

However, one noted that his art was constantly improving. During these years, between seasons, he was singing regularly in Paris (Théâtre de Nations), acquiring the best attributes of the French School and adding to his repertory operas such as 'Sigurd,' 'Herodiade,' "Simon Boccanegra,' 'Aben Hamet,' and 'Le Cid.' It was in the last-named work, in November, 1885, that his brother Jean, creating the title-role, won his first genuine triumph as a tenor and became the prime favourite of Parisian opera-goers. This, by the way, was not at the Italiens, but at the Opéra (that is, the Académie Nationale de Musique), where Edouard had made his début as Mephistopheles in the previous April. Then, a couple of years later, came Harris' season at Drury Lane, already referred to, when the two brothers, after a sensational opening (June 13, 1887), in 'Aïda.' appeared together in 'Les Huguenots,' 'Faust,' and 'Lohengrin'- all sung in Italian- and by means of their maginficent voices and superb art helped to rekindle the dying flame of the lamp of Opera in this country. The immediate outcome of their triumph was the reopening of Covent Garden in 1888 and an added quarter of a century of existence for 'fashionable' and polyglot opera on the grand scale.

From that date it is almost impossible to differentiate between the careers of the two brothers down to their farewell of the stage, or even down to the tragic moment when the beginning of the war found them cut off from each other- Jean teaching in Paris: Edouard a prisoner with his wife and daughters on his estate at Garnek, in Poland, where he eked out a precarious existence until he died on May 25 last.

What a richly-endowed musical family were these De Reszkes! The sister Josephine, who was heard at Covent Garden as Aïda in 1881, was a fine dramatic soprano; she retired, however, when she married the Baron de Kronenberg, and died at Warsaw in 1891. There was, or is, a third brother, Victor de Reszke, who also had a good voice, but he never became a professional singer. He visited Jean and Edouard the year after they first became favourites here. They were men of singular refinement, intelligence, and taste, and it was a privilege to be in their society, to listen when they discussed their art and the technique of the singer or the actor. The great baritone, Lassalle, was at this time the constant companion of the two Polish artists, and they became known as 'le grand trio.'

An incomparable trio, indeed, they were! To have heard them together as Faust, Valentin, and Mephistopheles, or as Raoul, de Nevers, and Marcel, was an unforgettable experience. Later on came Plançon; but it was no longer quite the same thing. Like Edouard, he was a basso cantante, and their repertories were nearly identical (bar the German, which the Frenchman barely touched), so that when Lassalle left, Plançon could not replace him, and the 'grand trio' became a thing of the past. To assert, however, that Edouard's fame was second only to that of Plançon (vide The Times memoir on the 1st ult), was surely a complete reversal of the actual positions. Plançon, admirable artist and grand chanteur himself, always 'took off his hat' to Edouard. And he was right.

Apart from his glorious organ, Eduoard de Reszke possessed in an amazing degree the rarest attributes of the bel canto. Thanks to his marvelous breath-control, his command of tone-color, and his vocal agility, he could sing as lightly and delicately as a woman; or, when he pleased, he would emit a volume of rich, sonorous, powerful tone capable of penetrating through the loudest crashes of the modern orchestra. This was only one of the secrets of his remarkable versatility. Not alone as a singer but as an actor he had the gifts that enabled him to range with equal facility 'from grave to gay, from lively to severe.' His comedy was never heavy; that it was unctuous and full of humour, witness his Leprello, his Basilio, his Plunket; that it could combine the genial and sardonic with the dignified and picturesque, witness his striking Mephistopheles, modelled on Faure's original, yet having in it something of the daemonic that Chaliapin put into Boito's Mefistophele. Faure, Rota, and Plançon may have sung the Serenade as well, but no voice ever sounded at once so beautiful and so forbidding in the Church scene as Edouard's. His Frére Laurent in 'Roméo' was a simple joy.

His best proof of all-round genius (as in the case of Jean) came in he early 'nineties, at about the time when the brothers went to America for the first time. It was then that they dropped Wagner in Italian, studied him in his own language, and appeared with success in some of his noblest creations. Even the Germans had to admit the beauty of Edouard's Hans Sachs, the pathos of his König Marke, the rough grandeur of his Hunding and his Hagen. It was amid the glory of these later impersonations that he quitted the stage when Jean left it, in 1905: but he continued for a time to appear at concerts, and on one memorable occasion, he took part in a performance of 'Il Barbiere' in the tiny theatre attached to his brother's house in the Rue de la Faisanderie, when the Rosina was no other than

Madame Adelina Patti. Two illustrious artists then bade farewell to opera on the same night.

Much night be written of Edouard de Reszke as a man and a friend, but space does not permit. Let me, in conclusion, quote the following lines from Le Figaro of June 1:

Every admirer of this great artist, who as at once a born gentleman and a noble-hearted man, will be grievously pained by the news of his death, happening as it did during this period of grave crisis, far removed form many who were dear to him, under conditions that deprived his brother Jean, the faithful and glorious companion of his brilliant career, of the consolation of being able to aid him in his last days and to close his eyes at the end.

*Klein's date of birth for Edouard is two years later than the currently accepted one.