Vocal Art: How To Tune a Voice and Make It a Beautiful Instrument

Titles containing first-hand accounts of study with great singing masters—in this case Francesco Lamperti—are rare. I know. I’ve searched high and low for them. This is one.

Mary Augusta Brown Girard was born in 1836 to William and Martha Gage in Knox, New York, a town in Albany County just west of Albany, New York, and died in San Francisco, California, in 1926, having married twice: first to Augustus Brown in 1867 when she was 30—and with whom she had a son who died at the age of nine—then to Frank Girard.

Girard was fifty-seven when she published Vocal Art: How to Tune a Voice and Make It a Beautiful Instrument: Advice to Singers in 1893—a year after the death of her most influential teacher, Francesco Lamperti. Girard later updated the title to The Psychology of Vocal Art: How To Train a Voice and Make It a Beautiful Instrument for Speaking and Singing in 1920—six years before her death at the age of ninety.

Girard’s text went through three printings—1893, 1909, and 1920—but does anyone know it today? No. And what a book it is, one which reveals the central teachings of Lamperti to a nation hungry for the wisdom of an eminent old-school master.

Girard studied in America with Madam Nube, Anna Bishop, and Carl Formes before losing her voice to bronchitis, which sent her searching for a scientific method to regain vocal ease.

I went from master to master, hoping to find some scientific method by which I could know how to place the tones at all times. Each assured me that with his superior method, I should gain all that it was necessary to know.

I would practice faithfully for months until in sheer desperation, I demanded more definite understanding and result. I would be assured that so scientific a method as I was in search of did not exist, that each must learn from his own experience.

—Girard, Augusta Brown. Vocal Art: How to Tune a Voice and Make It a Beautiful Instrument: Advice to Singers (1909), p. 11-12.

Girard studied Anatomy, Physiology, and Hygiene (acoustics did not exist as a course of study for another century), thinking this would give her insight into her problem, and even obtained a degree in the Woman’s Medical College of Chicago, then another course in the College of France, where she studied hysteria with Louis Pasteur.

Continuing her search, William A. Gage, Girard’s brother, funded Girard’s extended study in Europe, where she worked with Mathilde Marchesi and Professor Bears in Paris, Signor Polini in Naples, Madam Potentini in Rome, Antonio Sangiovani in Florence, and most importantly, with Francesco Lamperti in Milan, who gave her the answers she sought.

Lamperti’s great aim was quality, softness, sweetness. He allowed his pupils to sing only in the softest voice. “Sutte Voce,” “Sutte Voce,” (softly) was his favorite expression.

“Float the voice above the breath.” That is, make the tone in the pharynx. Florid music was his delight.

—Girard, Augusta Brown. Vocal Art: How to Tune a Voice and Make It a Beautiful Instrument: Advice to Singers (1909), p. 13-14. It should be noted that Lamperti spoke Milanese, a dialect, rather than Italian as we know it today.

Girard gives us the key to Lamperti’s method, which involves a specific species of voice placement.

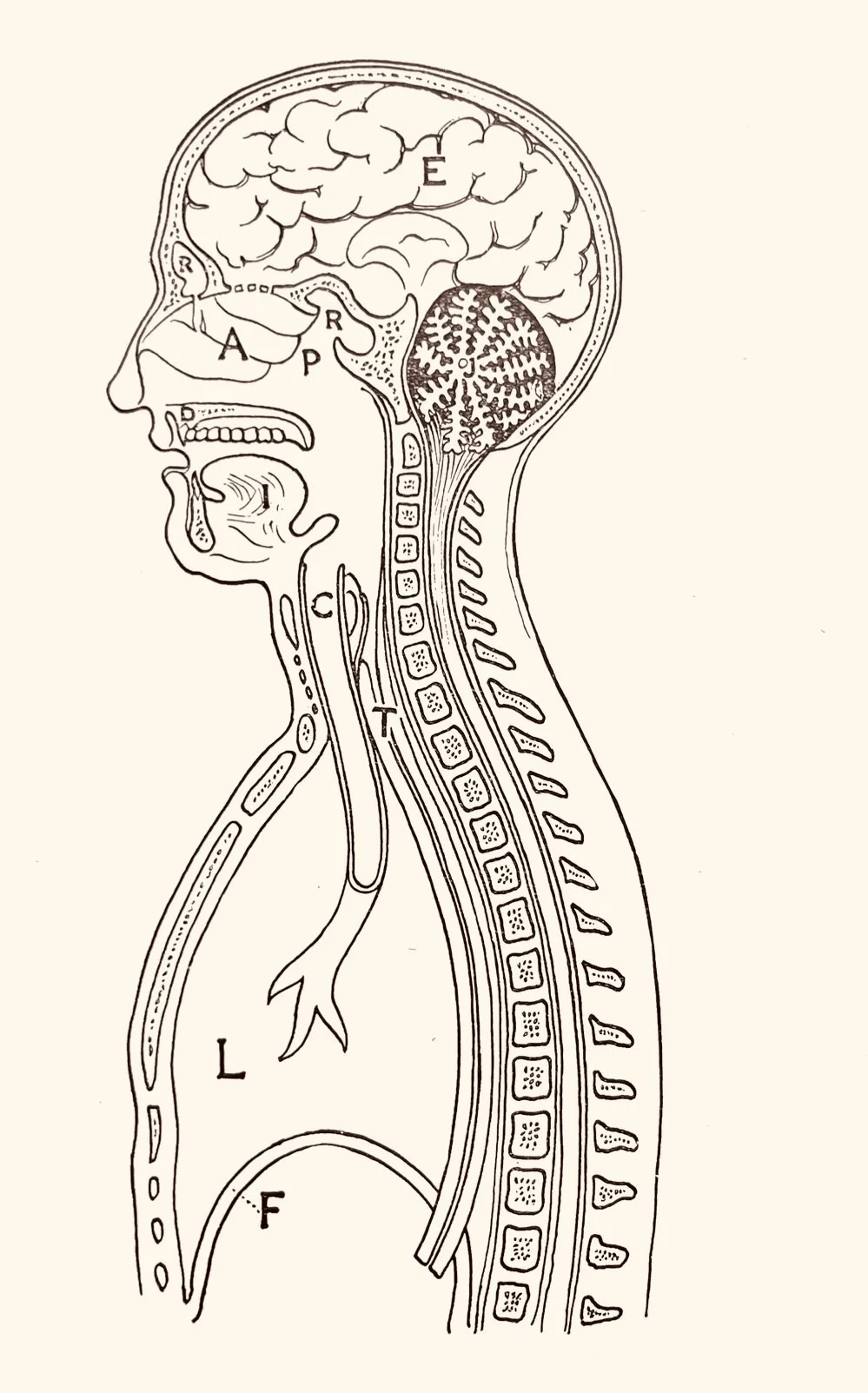

I have heard students regret that they could not have studied with the Old Master. Yes, those who had the opportunity were fortunate for the discipline was as beneficial as the lessons in singing. Lamperti never gave his pupils any compliments or encouragement only to stimulate greater ambition, exertion and interest to complete one thing at a time. He would keep a pupil weeks on a single phrase, if necessary; there was no other way but to complete it or step out, but as I said before, he would transform a weak, tuneless voice into a thing of beauty that was a delight to listen to. You ask: How did he do it? First, by mastering control of the breath, the jaw, tongue articulation; then, by keeping in mind an ideal tone—first as soft and sweet as possible, with the tongue in the bottom of the mouth, with the tip resting firmly at the roots of the lower teeth, the whole jaw relaxed completely as if dislocated at its point of junction, the mind directed to the cerebelum where all sound is supported, just back of the throne of the pharynx. Locate it exactly, first. Draw an imaginary line through one ear to the other, then from the upper front teeth to the back of the head, where the lines cross each other, is the life center for tone. Sound the letter E, and direct it to this point, just where the head begins to round up, see plate J. Never sing a note without first placing it there.—high or low; have that point for support, placing. No matter how high the note on the scale my be, have the placing at this point only.

—Girard, Augusta Brown. Vocal Art: How to Tune a Voice and Make It a Beautiful Instrument: Advice to Singers (1909), p. 79-81.

Girard, Augusta Brown. Vocal Art: How to Tune a Voice and Make It a Beautiful Instrument: Advice to Singers (1909)

Longtime readers of VOICETALK will know that Girard’s curious turn of phrase—the throne of the pharynx—echos the teaching of Francesco Lamperti’s son, Giovanni Battista, in William Earl Brown’s Vocal Wisdom: Maxims of Giovanni Battista Lamperti (1931), G. B. Lamperti calling the area above and behind the soft palate “The Spot”.

Girard further clarified the throne of the pharynx in her text.

The first organ involved in singing is the nose. Close the lips; take a breath through the nose. Where do you feel it first?

At the bridge of the anterior and posterior nares. Back of the bridge, and back of and above the palate, is the throne of the pharynx, and this is another strong point for the singer; one of the two, first important points to be considered (never to be lost sight of; never ot be let go of). It is the first, last and always (not only in making the head tones, but all the tones, from the highest to the lowest, must be supported here). Feel that this is the abiding place of tone. We will call it the throne of the singer, for as long as he has control here, he has control of his voice, but when he has lost control of this point, he has lost his kingdom as a singer.

—Girard, Augusta Brown. Vocal Art: How to Tune a Voice and Make It a Beautiful Instrument: Advice to Singers (1909), p. 33-34.

Of course, as you are reading these passages, you may be thinking: “Science tells us the only resonator is the vocal tube, the passage from the lips to behind the larynx. What is this “throne the pharynx” and back of the head nonsense?”

These matters involve the study of psychoacoustics, the perception of sound, and its effect on the body and mind. Astute readers will know that the auditory perception of the Singers Formant has been observed where Girard located it—above the soft palate, in the center of the head, or with Girard’s terminology—at the throne of the pharynx.

Girard also tells us Lamperti’s teaching was like that of other masters, with one exception.

Lamperti holds him like a vise till he has finished the first essential, so that he can never fall back. Now he is ready to go on to another branch, but it must be just as complete until he has mastered every condition favorable to song—vocal requirements and himself as well. This was Lamperti’s secret. The student’s first teacher may have understood just as well what was required and just as competent in knowledge as to what was necessary, but Lamperti not only taught him what to do, but made him do it then and there. His motto was, “Do it now.”

—Girard, Augusta Brown. Vocal Art: How to Tune a Voice and Make It a Beautiful Instrument: Advice to Singers (1909), p. 117.

Voice teachers today, especially those in conservatories, do not have the luxury of holding their students to the fundamentals as taught by Francesco Lamperti. Why? Repertoire requirements. Many of them, I warrant, would disavow Lamperti’s teaching as old-fashioned, obsolete, and unscientific even though science shows us how to understand it.

Margaret Harshaw taught me Girard’s “throne of the pharynx,” calling it “The Star:” while Judith Doniger, Harshaw’s fellow student with Anna Schoen-René, confirmed the latter’s teaching when she tapped a forefinger just above and in front of her right ear and said: “This is where we make most of our tones.”

This is the teaching of the old school and the Garcias and Lampertis.

I take great pleasure in bearing testimony to the worth of my esteemed pupil, Dr. M. A. Brown Girard. Nature has endowed her with a rich mezzo soprano voice of rare quality, a musical ear, critical judgement and artistic taste. With her untiring zeal, her great intelligence and love of analysis, her ability to master difficulties, her experimental knowledge gained by aid of the laryngoscope and stethoscope, her familiarity with the anatomy of the voice and the laws governing sound and her rare ability to impart to others, should make her a superior instructor. — CAV FRANCESCO LAMPERTI, Professor of the Royal Conservatory of Milan, 1890.

—Girard, Augusta Brown. Vocal Art: How to Tune a Voice and Make It a Beautiful Instrument: Advice to Singers (1909), p. 151.

Find Vocal Art: How to Tune a Voice and Make It a Beautiful Instrument: Advice for Singers on the Download page.