The Lamperti Lineage: Jane Meyerheim

Jane Meyerheim (neé Henri Jane —1864-1934) was born the same year as Anna Eugénie Schoen-René and, like Schoen-René, studied with Francesco Lamperti, the most famous vocal maestro in Italy during the 19th century.

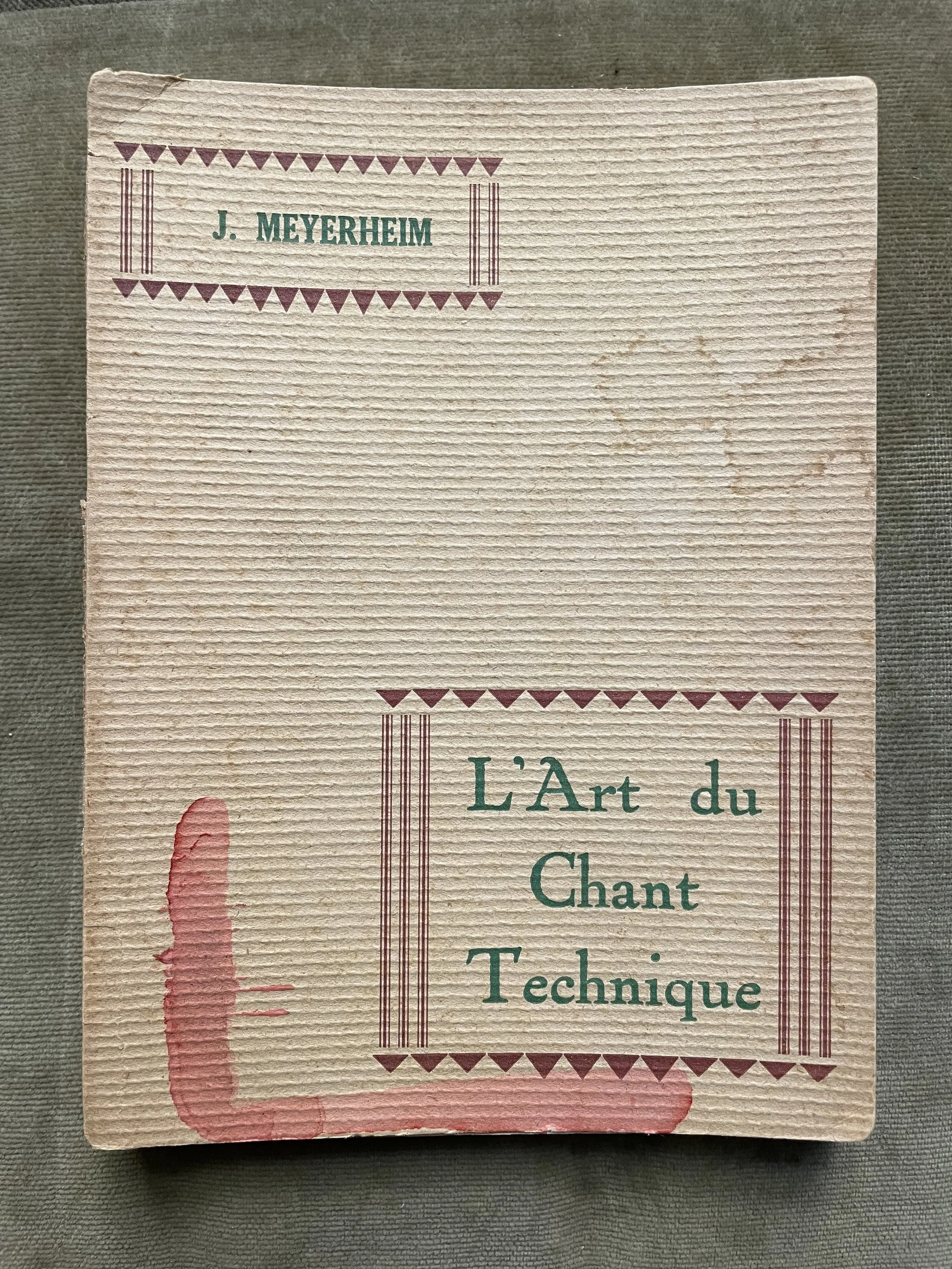

Meyerheim taught singing in Paris and wrote plays and several books on singing, including L’Art du Chant Technique (1904). Five years after her book was published, its growing acclaim resulted in an article about Meyerheim and the art of singing that appeared in many papers, including The Daily Province in Vancouver, British Columbia (1909). Find this article below with an article that appeared nearly a decade later in the Musical Courier in 1917.

Learning to Sing Without a Master

Jane Meyerheim (1864-1934)

I was interested, reading in the column of the “Information Bureau" of your valuable paper an inquiry as to whether it was possible to study singing without attending a school or having a private instructor, and what books would be advised. There is a book which at the present moment is attracting a great deal of attention and several letters have appeared in the New York Herald in favor of it. The book is called “L’Art du Chant Technique,” the author of which is Mme. Meyerheim, an English lady educated in Italy, a pupil of the Milan Conservatory and of the famous Francesco Lamperti. She has, with consummate skill and thorough knowledge of the subject, written an exposition of the old Italian method and proved it to be based on the art of breathing. The book is being used by many of the greatest teachers to help their pupils to acquire the correct way of breathing. Anyone after studying this book will not find it difficult to apply the method and will be amazed at the results. The technic of breathing undoubtedly occupies a promiment place in the art of singing, as an understanding of the proper use of the breath is an important requisite; but to know how to breathe properly does not constitute the art of singing. That it is possible to learn how to breathe by reading and studying a book is also conceded, yet, in order to become a finished singer, proficient in every detail of singing technic, the services of a teacher seem absolutely indispensable. One has only to watch the work of pupils who take from two to six lessons a week to realize how easily and quickly they develop “bad habits” even in the short time that they practise at home away from their instructors. Few pupils hear their own tones in a way to realize their faulty production; that is why a teacher is so necessary. What patience is required when, lesson after lesson, the same explanations have to be given, the same faults noticed, the same exercises gone over and over, again and again! To become a successful singer, whether for opera or other public work, requires an enormous amount of time and patience on the part of both teacher and pupil. That is why those who do not study seriously are not desired as pupils. That a book such as described above can be of service to students is no doubt true, but its benefit would be greatest if used in connection with a teacher. If a student could learn to sing from reading a book and practising what it teaches, the long years of study which are considered requisite now, might be done away with and competent singers turned out in a few months. The author of the book, having, studied with Francesco Lamperti, must realize how impossible that is. If the book could hear and thus correct the mistakes of the pupil, that would be another story. The limitations of those who study, whether it is singing or any other of the arts, makes any quick, and at the same time sure, progress over the road to learning practically out of the question. What is the result of self-teaching? A beautiful voice that could have been made “great” is not developed to its highest possibilities, so that while one admires the voice there is always the lack of training shown, and heard, in every note sung. To the musician the voice is spoiled by lack of training. The natural beauty is there, but the singer does not know how to use the fine organ at his command.

—” Learning to Sing Without a Master,” The Musical Courier, December 13, 1917, page 48.

The Teaching of Singing

There is scarcely one of the well-known music teachers of Paris, says a correspondent of a London paper, whose list of pupils does not include girls from England, Canada or the United States. It may interest readers of these countries to listen to a few unadorned truths regarding singets and singing from one who, by her authority and experience, is imminently qualified to speak on the subject. Mme. Meyerheim, herself a pupil of the celebrated Francesco Lamperti, is known on the continent as the author of several text books on singing, and as a most painstaking professor in her art. She is accustomed to speak plainly and when I asked her the other day how many of the young ladies who imagined they were destined to become operatic stars really came to the front, she answered without hesitation:

Meyerheim on Breathing

The best way to learn to use abdominal breathing is to take a bellows. By lifting the handle, you can see that the bottom of the bellows disappears. To breathe, the body takes the same position; the abdomen disappears and the chest rises. Each time you breathe, the same movement occurs. However, care must be taken to ensure that the abdomen is erased at the same time as the chest rises. The chest should not be inflated first, as this would produce a contrary movement and the abdomen would also swell, instead of flattening. To facilitate this movement, you must lower your shoulders before each new breath and breathe through your nose, mouth closed, before you begin to sing. It is this movement of regular breathing which develops the chest, fortifies the lungs and consequently health. — L’Art du Chant Technique (1904), p 11.

“A least fifty percent of the English and American girls who come to Paris to study have no capacity whatever. Few teachers, however—very few—are honest enough to tell them this. On the contrary, they encourage them to embark on a professional career, and take their money for years, misleading the unfortunate girls into the belief that one day they will be as famous and as rich as Melba, while the truth is they have not enough voice to sing in a drawing room. these teachers who at in this way justify their conduct by the argument that if they sent applicants away after telling them they lacked musical capacity, they would only fall into the hands of less scrupulous professors, who would keep them till all their money was gone. This may be quite true, and it is only fair to add that many aspirants with inflated notions of their vocal abilities would not thank a teacher for telling them the truth about their voices, but would much rather part with their fees to someone who flattered their vanity and predicted a glorious career for them. The consequence is that in numerous cases English and American girls—as well as those of other nationalities—waste years in the conviction that they are training for grand opera, while in reality they are only spoiling their voices, ruining their health, and wasting their money. Then, when their money is gone and their health is broken down, they are ashamed to go back home again, and the end of many of these poor girls is better left untold.

“What is perhaps sadder still is that girls who come to Paris with good voices frequently ruin them through bad tuition, that is, taking lessons from incapable professors. The average fee for a singing lesson from a Paris teacher of any pretentions is 29s. and M. Jean de Reszke gets a couple of soveriegns for every twenty minutes he devotes to a pupil. But in spite of the high fees and the every-increasing numbers of the modern professor, the vocal art continues to decline.

“What, in your opinion,” I asked, is the reason of that decline?”

“Francesco Lamperti,” she replied, “ascribed it in large measure to the influence of Wagner’s music. My personal opinion is that the forsaking of Italian music has more than anything else contributed to the decline of the vocal art. To be able to sing Italian music all the qualities of that art are requisite: a pure voice, perfect execution, vocalization, scales, trill, style and lastly, genius, by which I mean the soul. In order to execute Wagner’s music not so much is demanded. A voice—and a powerful one—is imperative, also exceptionally strong lungs to sustain it. When this voice is well placed, and the possessor of it knows how to declaim, the rest can be dispensed with. If only modern French singers, with their artistic qualities, their charm, their diction, and their personality, would return to the Italian method, which would give them the science they lack, they would become perfect artists.”

Madame Meyerhiem attaches enormous importance to breathing. “Unless you know how to breathe,” she says, “you may know everything about music and yet nothing. The first thing to learn in the art of singing is breathing. In Paris, for instance, everyone has style, but with a few exceptions no one knows how to breathe. If people would only take the trouble to learn how to breathe properly, there would be much less illness and a great many fewer consumptives. In singing, however, it is not enough to know how to breathe, one must learn also how to keep the breath back. This is managed by singing from within and pressing the diaphragm on the muscles of the abdomen, and at the same time directing the voice backwards. When one does not husband the breath everything collapses.

“One sometimes sees singers on the stage and on the concert platform making horrible grimaces,” I remarked. “I’m sure if they realised how much these facial contortions distracted from their art, they would endeavor to counteract them.”

“I quite agree with you,” said the eminent musician. “It is essential that a singer when before the public should look graceful, pleasant, and perfectly at ease. All stiffness should be avoided. The body and head should never be thrown back; that is a bad habit of many artists. In the first place, it is not graceful; secondly, those who adopt this attitude sing on their chest or on their throats, or both. The head would be slightly bent and the chin drawn in. As to the face, it is not necessary to force a smile, as some persons do when sitting to a photographer, but is indispensable to look amiable and gracious, as when offering a flower, or instance. The eyes should be sweet and tender-looking, and in the chromatic scales will naturally take a more intense expression, as if imploring some special favor. The position of the body and the expression of the face are what may be called the prelude of singing; they certainly add to its charm. I have seen singers remarkably for their ugliness become positively beautiful the moment they began to sing, and in the same way I have seen pretty faces made hideous through the strain they put upon themselves to produce their notes. The first-named were great artists, but those who lack the power of facial expression can never be true artists. Many years ago I remember hearing the celebrated composer Theodore Ritter say to a pupil who was playing Chopin without expression:

“Voyes vous, non enfant, qaund un Joue du Chopin il faut avoir des larmes dan les doigts.” It is the same in singing: one should have tears in the voice as well as in the eyes.”

— “Teaching of Singing,” The Daily Province, Vancouver, British Columbia, Saturday, May 15, 1909.

Find Meyerheim’s L’Art du Chant Technique (1904) on the download page. If you don’t read French, you can download the Google Translate app onto your phone and then scan and translate the text page by page. You will find Meyerheim’s instructions on breathing and a great deal more.

Curiously, Meyerheim’s book was so influential that whole chapters were lifted from it and published as “How to Sing by Enrico Caruso” in 1913 (The John Church Company, London). Caruso did not write this book and had to go to court to defend himself from litigation from Meyerheim.