Lamperti at Home

Although it is not over a quarter-of-a-century since Lamperti ceased to teach at the Conservatoire at Milan, he still receives private pupils, who come to him from the United States, the Colonies, and different parts of Europe.

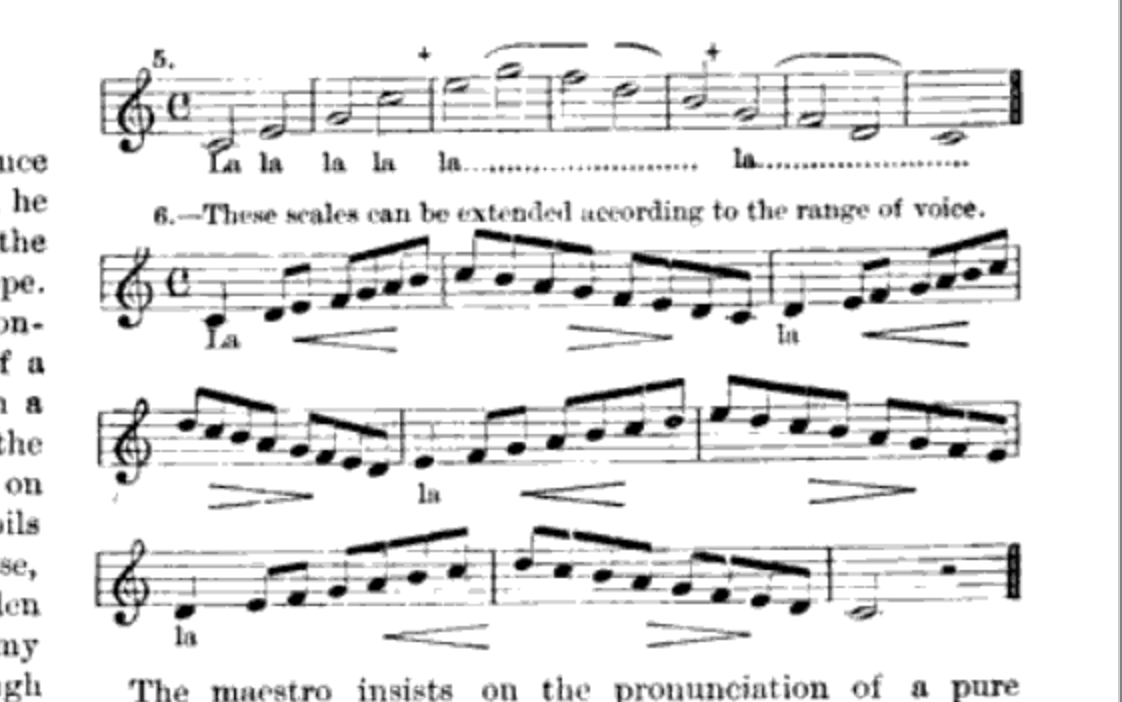

He is certainly a man of remarkable activity of mind considering his advanced age; so I found on the occasion of a recent visit, prompted by a desire to receive from home a short course of lessons. For the last eighteen years the maestro has spent the summer months at Cernobbio on Lake Como, wintering usually at Nice or Milan, his pupils following him from place to place. The maestro’s house, built by himself, stands in the midst of a large garden a few hundred yards from the lake, and thither I went my way on a morning of my first lesson. Passing through the lodge-gates, a gravel path leads me to the “Villa Lamperti.” Entering I am confronted by a comparatively juvenile-looking bust of the great teacher placed in a recess of the hall. A knock at the door, and I am in the presence of the maestro himself. As he comes forward to greet me, I observe that he is a feeble-looking old man. The lesson does not immediately begin, for the maestro points out to the me, with evident satisfaction and pride, the portraits of his many distinguished pupils which adorn the walls. I do not fail to notice also the two fully-sized oil portraits of the maestro and Madame Lamperti, painted by a Milanese artist. Natrually the maestro is very proud of Albani, and takes special delight in showing all new comers the latest picture of as Desdemona, which the prima donna thoughtfully sent this year. This over, the lessons begin. All the pupils attend the morning class, which commences about nine o’clock, and although each does not receive a lesson, invaluable hints can be gathered from listening to and observing the faults of others. With Madame Lamperti at the piano, and the maestro seated in an armchair, the pupils begin with vocal exercises, a few of which are given below: —

The maestro insists on the pronunciation of a pure Italian a. To attain this it is necessary that the throat should perfectly loose, and the mouth well open. No one has any idea how difficult it is to sing this vowel sound until he has tried. Let him begin an exercise on a, and the chances are that before he has sung many notes his mouth will partially close, and he will find that the a has degenerated into the Italian o. As the maestro is found of remarking, “Ah, you English geese, you always sing o.”

These exercises are followed by solfeggi, or in the case of the more advanced pupil, by an aria from one of the operas, the maestro now and again suggesting cadenzas suitable to the individual capabilities of the singer, and such only as were countenanced by the old masters. The studies are more or less satisfactorily performed, corrections are given at all times when needed, and these, in case of the less advanced pupils are not infrequent. The maestro, whose hearing is particularly sensitive, does not hesitate to add force to his remarks by aid of a small stick, when he thinks the pupil of such an attention! He strongly insists on deep diaphragmatic breathing and complete control of breath my means of the abdominal muscles, so that the breath by emitted gradually and without jerks. All exercises too must be sung legato. In controlling the breath the throat should remain neutral—perfectly loose. When once the throat is stiffened the note becomes harsh, and the tone is destroyed.

Imperfect breathing, and consequent effort to control the breath by means of the throat, forces the note to the front part of the palate, and with the result a frontale and nasal quality is produced. On the other hand, a breath properly taken and held with the throat unconscious, causes the note emmited from the larynx to be impinged upon the whole of the palate, and a pure vocal tone is produced vibrating towards the back of the head. Fontale singing is so general a fault of modern singers who go to Lamperti that the sound of the word is continually ringing in the air. It must be admitted that if the whole of the palate—the vocal sounding-board—be not utilized, the note produced must as a natural consequence be imperfect, and this is actually the case with frontale singing. Let the vocal student, then, breathe well and he will sing well.

Lamperti came to London a few years ago at the request of Albani, who could not get away as usual owing to her contract with the elder Gye—her after father-in-law. The prima donna received lessons of Lamperti twice a day, morning and afternoon, an hour each time. In the evening she sang at the opera. The maestro used to trace her improvement from day to day, and suggest alterations in her style and cadenzas. During Lamperti's stay in London many fresh pupils came to him, the late Countess of Rosebery among the number, who, it is said, paid as much as five guineas a lesson. It may interest some to know that the maestro abominates the English climate, and always says, when London is talked of, " There are two things in London you have not—the sun and a good cook." Lamperti is a Cavaliere of the Order of Saints Maurizio and Lazzaro ; Honorary Master of the Class of Composers in the Congregation and Academy of Rome ; Cavaliere of the Royal Order of Isabella, and Commendatore of the Royal House of Spain. He too is the author of several works on vocal culture, vocal exercises, &c. Lamperti';- "Art of Singing," published by Ricordi, can be strongly recommended to all earnest students. It contains all the precepts the maestro is constantly impressing upon his pupils. Madame Albani, writing iu 1875 of his published treatise on singing, says: "To say that I appreciate the work it is sufficient for me to state that I am a pupil of the Maestro Lamperti, and that I owe to him and to his method the true art of singing, so little known in these days." It is satisfactory to remember that the old Italian method cannot die out while we have Lamperti's distinguished pupil, Mr. William Shakespeare, still teaching in our midst.

Francesco Lamperti was born in the early part of the present century. His father was an advocate, and his mother a prima donna of considerable repute. Showing remarkable musical ability, he was at an early age placed under Pietra Rizzi, of Lodi. In the year 1820 he entered the Conservatoire at Milan, and studied harmony and the pianoforte. As a young man he used to play the organ in Milan Cathedral. At the age of 18 he commenced to teach singing, and his success was such that his fame as a teacher rapidly spread, and he was appointed one of the directors of the Teatro Filodrammatico at Lodi. There, as now in Italy, the chorus members of the company were chosen from the "contadini" (peasantry). Selecting the most promising of these, Lamperti educated and trained their voices, and not a few developed into famous singers. In this way many were brought to the front whose reputation would not otherwise have extended beyond the narrowest limits. So great was his success (hat pupils flocked to him from all parts of Europe, and at Lodi he trained many of the most distinguished operatic vocalists of the day. In 1850 Lamperti was appointed by the Austrian government Professor of Singing at the Conservatoire at Milan. Here he taught for a period of 25 years, retiring in 1875 on a pension. Since that time he has entirely devoted himself to private teaching.

We select the names of a few of his most distinguished pupils, and although some of these are probably not well known to the present generation of English musical students, the names of others are familiar to all:—Jeanne Sophie Lowe, the Sisters Cruvelli, Hayes, Artot, Tiberini, La Grange, La Borde, Albani, Stoltz, Campanini, Aldighieri, Shakespeare, Sembrich, Delia Valle, Van Zandt, and Isidore de Lara.

It is evident that a system which can produce such an array of talent must be based upon sound and scientific principles. Lamperti was intimately connected with Donizetti and Bellini, and was a friend of Rubini, the most celebrated of modem singers (of whom it is said that "he was born for Bellini,'' to such a degree did he influence this composer); a friend also of Malibran, one of the most distinguished contralto singers the world has ever heard, and of Pasta, a splendid soprano. Associated thus with the great singers of the past, Lamperti follows the method of the old Italian school instituted by Porpora, Farinelli, Crescentini, &c. A loyal disciple of this old school, and a close observer of the great singers contemporary with him, he bases his teaching upon the study of (1) Diaphragmatic breathing as opposed to the clavicular or chest breathing; (2) Perfect control of the breath by means of the abdominal muscles; (3) As a consequence of the above—a perfectly loose and unconscious throat.

The old Italian school of singing may be said to have been instituted about the middle of the 15th century, although it seems that no definite method of instruction was adopted until the time of Caccini (1588-1640). Indeed, to this great teacher and to his labours was due the firm establishment of a method of vocalisation which for a time placed Italian singers far in advance of all others. A few years later one Pistocchi (1059-1720) flourished at Bologna, and established for himself a high reputation as a singing-master. Contemporary with him was Scarlatti (1695-1725), one of the greatest lights of the 17th century, and the founder of modern opera. Of his pupils Porpora (1686-1760) was the most celebrated. As a singing-master and in the excellence of his pupils, Porpora was unrivaled. He is said to have been the greatest master that ever lived, and no singers before or since have sung like his pupils, who included Farinelli (1705-1782) and Caffarelli (1703-1783). A pupil who studied with Bernacchi (the pupil of Pistocchi and the "King of Singers") writing of Farinelli, says: "The art of taking and keeping the breath so softly and easily that no one could perceive it, began and died with him." Certainly Farinelli, who was a male soprano, must have possessed a remarkable voice, some going so far as to aver that he was as superior to the great singers of his own period as they were to those of more recent times; in short, the greatest singer that has ever lived. The next of the famous maestri were Marchesi (1755-1829) and Crescentini (1766-1846), whose works, consisting mostly of vocal exercises, are still in use.

These were the men who originated and perfected the old Italian school of singing. They were great singers and good musicians, and therein lay the secret of their success. These celebrated artists as they left the stage took to teaching, and so appeared again, as it were, in their pupils. In this way the pure style of vocalisation was handed down from master to pupil. Such excellence in the art as was then attained could only have resulted from a thorough knowledge of the human voice and its peculiarities. The gradual development of the vocal organ, and not the forcing of all the powers, was one of the special features of their school. There was no hurry. No time was considered too long to spend in training the voice. Porpora is even said to have kept one of his pupils (Caffarelli) six years to one sheet of exercises. The result of this graduated and lengthened study was that the voice responded with the precision of a perfect instrument. It was this long and uninterrupted course of training that furnished Italy with so many of the best singers and teachers.

With this school the elder Lamperti has been directly and closely associated for many years, and he is now generally regarded as the last of these old Italian masters. As my visit this summer was paid with the special object of learning something of his method of instruction, I hope that my experiences of the famous maestro may not be devoid of interest to the readers of the Musical Herald.

—The Musical Herald, November 1, 1891, p. 326- 327

The article above was contained in a link in one of my first blog posts at VOICETALK and now appears in its entirety. Written in 1891, Francesco Lamperti lived until May of the following year.

Observant readers will notice that Lamperti’s pedagogy regarding singing towards the back of the head is a main feature within Girard’s book Vocal Art: How to Tune a Voice and Make It a Beautiful Instrument.

Observant readers will also notice that Manuel Garcia the Elder taught the second exercise above, which appears in his book and can be found on the download page. The only difference is that the Garcia singing school eschewed using a consonant.

Lastly, this curious blogger found himself on Google Maps looking for Lamperti’s house—he has the address—and found that it seems to have been in what is now a park. One day, he’ll go to Cerbnobbio to see for himself.